Eranthis hyemalis (L.) Salisb. – Winter aconite

by Peter Williams

“As the days lengthen, the cold strengthens” is an old country saying that reflects the fact that, after the winter solstice that marks the shortest day and the onset of astronomical winter, the temperature falls as daylength slowly begins to increase. It is at exactly this time that the cheerful golden flowers of Eranthis hyemalis make their very welcome appearance as the harbingers of spring.

The winter aconite is a tuberous herbaceous perennial belonging to the Ranunculaceae family. It is one of eleven species in the genus Eranthis and is a native of deciduous woodlands in southern Europe from France to the Balkans.

Both the scientific and common names of this lovely small European native have been surrounded by contradiction and confusion. The botanical name is a mixture of Greek and Latin and translates as the ‘spring flower of winter’. Gerarde in his Herbal of 1597 referred to the species as Aconitum hyemale with the common names, Winter Woolfes bane, Hibernum and Winter Aconite. He reports that “It groweth upon the mountaines of Germanie: we have great quantitie of it in our London gardens”.

Gerarde thought it was closely related to, and hence just as toxic as the extremely poisonous monkshood or wolfsbane, Aconitum napellus. He thought this because of the similarity of the leaf shapes and fruiting bodies (follicles).

On its toxicity he wrote “This herbe is counted to be very dangerous and deadly: hot & drie in the fourth degree”. Whilst winter aconite does contain a range of potentially harmful alkaloid poisons, it is not considered a dangerous plant. No cases of poisoning have been recorded in humans but I did come across the case of an unfortunate 12year-old dachshund with the propensity for digging that became very ill after excavating, and then eating, winter aconite tubers!

Later botanists noted that winter aconite and hellebore flowers had very similar floral structures and both produced seeds in follicles. It was thus named Helleborus hyemalis by Linnaeus. It appears with this name in the first edition of The Botanical Magazine in 1787 (the forerunner of Curtis’s Botanical Magazine). However, recent genetic analysis has shown that the diminutive aconites are more closely related to the statuesque Actaeas (formerly Cimicifuga) than to the hellebores.

The currently accepted botanical name for winter aconite – Eranthis hyemalis (L.) Salisb. records a further name change in 1807. The attribution, (L.) Salisb. after the generic and species names, indicates that the Linnean name, Helleborus, was changed to Eranthis by Richard Salisbury. Salisbury was the son of a Leeds cloth merchant and considered to be a disreputable character in botanical circles. He personally underwent a name change because he was born Richard Anthony Markham but changed his name to Salisbury in an attempt to inherit a fortune from a distant relative of his mother.

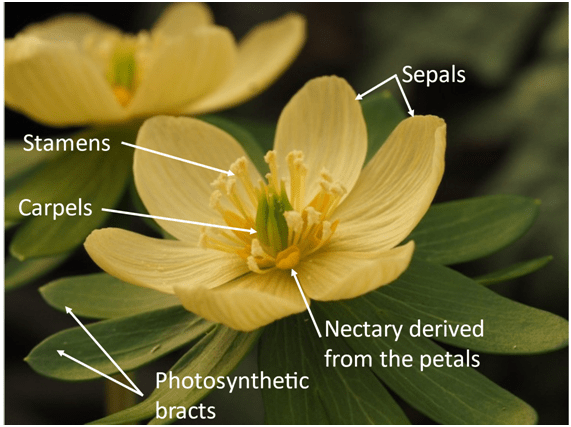

Each flower stem bears a collar of green photosynthetic bracts that maximise energy capture to fuel the growth of the plant and production of large seeds that are shed in April/May. All above-ground plant parts die back by June to leave summer-dormant underground tubers.

Seeds shed in one season germinate in spring the following year and under favourable conditions, carpets of aconites become quickly established. There does not, however, seem to be a consensus about what constitutes favourable conditions for aconites and some gardeners report that they are difficult to grow. I have found that winter aconites grow well on my acid, sandy soil and thrive both in areas where they receive very little direct sunshine (like the north sides of an evergreen hedge) and in open, south-facing areas in full sun. They also grow well on the heavy, chalky slopes of the Yorkshire Wolds so appear to be indifferent to soil pH and texture. The one feature shared by the areas in my garden where they thrive is that they are very dry in summer. Perhaps the key to initial establishment is to plant potted, actively growing specimens or freshly dug dormant tubers that have not become dry. Where plants have become established, care should be taken not to disturb emerging seedlings by spring cultivation and tidying operations if the carpeting effect is desired.

Weed control is probably best achieved by use of autumn mulches rather than spring hoeing. This approach is particularly suitable where winter aconites are established under deciduous shrubs where their presence in spring is a great bonus. With my neglectful approach to gardening, Eranthis self-seed freely and establish well in the untidied woodland beds and have successfully invaded the neglected margins of my gravel drive.

There have been a number of selections of Eranthis hyemalis that exhibit distinctively paler or richer colour forms than the norm and the sulphur-yellow variety ‘Schwefelglanz’ is often seen (Fig.3). Garden centres now frequently offer E. cilicica which is very similar to E. hyemalis but is slightly later flowering and originates from Iraq and Turkey. Hybrids of E. cilicica are becoming more common as is the attractive but sterile variety, Eranthis x tubergenii ‘Guinea Gold’. But for those amongst us who really enjoy a challenge, the beautiful but very difficult Asian species, Eranthis pinnatifida might be worth considering in an alpine house.

Images courtesy of Peter Williams